As long as there has been CGI in films and television, debates have raged about its artificial nature; however, what is different now is that the photorealism of the technology has evolved so much that it is no longer distinguishable from reality.

Central to the public awareness of a movie is that the cast and the studios do not want to risk dimming the star wattage – especially when hundreds of millions of dollars are at stake. “If you pay a lot of money for the talent that is also supposed to market your movie, you don’t want to cannibalize the actors’ marketing power by suggesting their performance wasn’t entirely real,” remarks Florian Gellinger, Owner and Executive VFX Producer at RISE. “That aspect is being pushed to the extreme when an actor actually does something crazy in the making of a movie – like jumping with a motorcycle off a cliff, and everybody is afraid that doubt might start to materialize if there is visual effects-related behind-the-scenes material available. All that, plus visual effects being a black box that is hard to understand for most audiences, make the studios’ choice to market films this way abundantly clear.”

“It’s become a status thing to make movies with minimal or no CGI,” notes Peter Howell, Movie Critic at The Toronto Star who

agrees with the idea that media coverage favors a negative point of view towards CGI. “Yes, because I think critics want to be seen as champions of old-school cinema: big screens, practical effects, celluloid film. Just as rock critics are champions of live shows, genuine musicianship and vinyl LPs.” Audiences are not as biased. Howell adds, “Moviegoers admire CGI if it’s done well and hate it if it’s done poorly. There’s no in-between.” A particular cinematic universe is not helping matters. “CGI is overused and is increasingly messy and boring. Most ‘multi-verse’ movies – I’m looking at you, Marvel – look like a

cake with too much icing.”

What is the definition for successful CGI? “It depends on the movie,” Gellinger notes. “CGI can be heavily stylized and artificial if that’s the concept of a film. But having something artificial-looking in a naturalistic picture would need to be justified by the story. Successful CGI has to have a reason why it looks a certain way, and that reason can be many things. In the end, when something doesn’t look right, it’s everyone’s fault to a certain extent – at least most of the time.”

“We’re in a weird time right now where CG is getting a lot of bashing in the press, and it’s not a fair criticism of what is being pulled apart because the reality is if you don’t like the CG in the shot, what you’re really saying is you don’t like the production design, set design and framing,” remarks Jay Cooper, VFX Supervisor at ILM. “There are a million different places where the CG is one component of what is being created, and what we’re seeing now is a knee-jerk reaction to artifice, and the thing that is the easiest to hang that criticism on is CG when it’s really a number of things. I debate whether those criticisms are appropriate. Sometimes it is. Sometimes it isn’t.”

Studios and directors need to be held accountable when CGI does not work out. “First and foremost, the studios and the directors have to make the right projects with the right teams,” states Allen Maris, Head of Visual Effects at Regency Productions. “The story needs to be there. Adding more visual effects will definitely not fix a third-act problem. Having more finals and less temps will not double your audience scores. Cutting the visual effects budget in half will also not help. Lack of planning will also hurt the process, as will not having enough time after turnover. The most problematic shots I’ve been involved with are ones that changed at the last minute, the production didn’t follow advice or the vendor wasn’t given enough time to work through the shot properly because of late turnovers.”

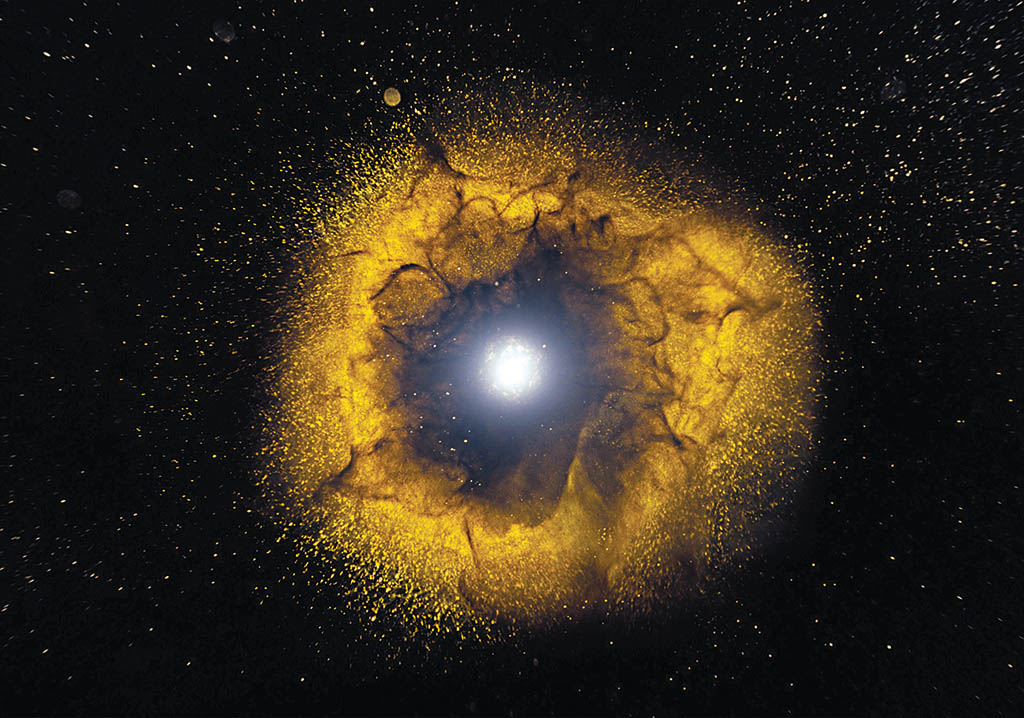

Christopher Nolan often finds himself in the center of the ‘No CGI” controversy, something he acknowledged back in 2011 when receiving the inaugural VES Visionary Award by stating, “It’s a great honor to be getting an award from the VES Society. I feel a little guilty receiving it from you guys as somebody who often appears in the press talking about my use of CG like an actress talking about her use of Botox. And I’m as dependent on visual effects, probably more so, than any other filmmaker out there.” In truth, his Oscar Best Picture-winning Oppenheimer represents a gray area of visual effects work. “Chris wants to have shots that he can cut into the film,” notes Andrew Jackson, VFX Supervisor for Oppenheimer. “I always keep that in mind when I’m shooting stuff, to frame it in a way that it can work without any [VFX] work at all. It’s great when that happens. A whole lot of shots got cut straight into film. Chris came out early on and said there is ‘No CG.’ To clarify, that means there were no computer-generated elements going into the compositing work. There were visual effects, in that a lot of those shots were a complex layering of multiple elements, but all of the input was photographic.”

“Some filmmakers are coveting what they see as a ‘badge of honor’ in downplaying or disregarding the vital role of visual effects in bringing their stories to life, and the VES is steadfast in proclaiming that VFX must be brought into the light,’’ says VES Board Chair Davidson. “VFX is an instrumental part of the creative process that works in service to story, and VFX bring stories to life that were once impossible. VFX artists and innovators deserve to be respected and recognized as agents of cinematic storytelling, in the same breath as other creative collaborators, and not cast aside as if they are detractors dispelling an illusion of ‘pure’ filmmaking. Speaking in one voice for our more than 5,000 members in 45+ countries worldwide, visual effects artists are proud partners in the creative process, and they need to be uplifted and given proper credit for their enormous contributions.”